Stellar Classification

Stellar Spectra

The light coming from a star can be analyzed by splitting it with a prism or diffraction grating into a spectrum, composed of a continuous spectrum superimposed with narrow spectral lines. Each line indicates the presence of a particular chemical element or molecule in the star, with the line strength indicating the abundance of that element. Stars can be classified into various classes, depending on their spectra.

Harvard Classification

The Harvard classification is based on lines that are mainly sensitive to the stellar temperature, rather than to gravity or luminosity. Important lines are the hydrogen Balmer lines, the lines of neutral helium, the iron lines, the H and K doublet of ionised calcium at 396.8 and 393.3 nm, the G band due to the CH molecule and some metals around 431 nm, the neutral calcium line at 422.7 nm and the lines of titanium oxide (TiO). The main types in the Harvard classification are denoted by capital letters.

| Class | () | Color | M () | R () | L () |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O | 33000 | Blue | 16 | 6.6 | 30000 |

| B | 10000 - 33000 | Deep bluish white | 2.1-16 | 1.8-6.6 | 25-30000 |

| A | 7300-10000 | Bluish white | 1.4-2.1 | 1.4-1.8 | 5-25 |

| F | 6000-7300 | White | 1.04-1.4 | 1.15-1.4 | 1.5-5 |

| G | 5300-6000 | Yellowish white | 0.8-1.04 | 0.96-1.15 | 0.6-1.5 |

| K | 3900-5300 | Pale yellowish orange | 0.45-0.8 | 0.7-0.96 | 0.08-0.6 |

| M | 2300-3900 | Orangish red | 0.08-0.45 | 0.7 | 0.08 |

The mass (M), radius (R) and luminosity (L) ranges indicated in the table are valid only for main-sequence stars. A common mnemonic to remember the class names is ‘Oh Be A Fine Girl Kiss Me (OBAFGKM)’.

Additional classes include

- W/WR: Wolf-Rayet stars

- P: Planetary nebulae

- C and S: Parallel branches to types G-M, differeing in their surface compostion

- L, T and Y: Red and brown dwarfs

These spectral classes can be further divided into subclasses, denoted by numbers 0 to 9. 0 is the hottest star in that spectral class, while 9 is the coolest. The spectral class of the Sun in G2.

MK classification

The Morgan-Keenana or Yerkes classification further distinguishes and classifies stars based on their luminosity

- 0 or Ia: hypergiants or extremely luminous supergiants

- Ia: luminous supergiants

- Iab: intermediate-size luminous supergiants

- Ib: less luminous supergiants

- II: bright giants

- III: normal giants

- IV: subgiants

- V: main-sequence stars (dwarfs)

- sd or VI: subdwarfs

- D or VII: white dwarfs

Our Sun is a G2V type star.

Peculiar stars

The spectra of some stars differ from what one would expect on the basis of their temperature and luminosity. Such stars are called peculiar. These include

- Wolf Rayet stars are very hot stars. The spectra of Wolf– Rayet stars have broad emission lines of hydrogen and ionised helium, carbon, nitrogen and oxygen. There are hardly any absorption lines. The Wolf–Rayet stars are thought to be very massive stars that have lost their outer layers in a strong stellar wind. This has exposed the stellar interior, which gives rise to a different spectrum than the normal outer layers.

- In some O and B stars the hydrogen absorption lines have weak emission components either at the line centre or in its wings. These stars are called Be and shell stars (the letter e after the spectral type indicates that there are emission lines in the spectrum). The emission lines are formed in a rotationally flattened gas shell around the star. The shell and Be stars show irregular variations, apparently related to structural changes in the shell.

- The strongest emission lines are those of the P Cygni stars, which have one or more sharp absorption lines on the short wavelength side of the emission line. It is thought that the lines are formed in a thick expanding envelope. The P Cygni stars are often variable.

- The peculiar A stars or Ap stars (p = peculiar) are usually strongly magnetic stars, where the lines are split into several components by the Zeeman effect. The lines of certain elements, such as magnesium, silicon, europium, chromium and strontium, are exceptionally strong in the Ap stars. Lines of rarer elements such as mercury, gallium or krypton may also be present. Otherwise, the Ap stars are like normal main sequence stars.

- The Am stars (m = metallic) also have anomalous element abundances, but not to the same extent as the Ap stars. The lines of e.g. the rare earths and the heaviest elements are strong in their spectra; those of calcium and scandium are weak.

- In the S stars, the normal lines of titanium, scandium and vanadium oxide are replaced with oxides of heavier elements, zirconium, yttrium and barium. A large fraction of the S stars are irregular variables. The name of the C stars refers to carbon. The metal oxide lines are almost completely absent in their spectra; instead, various carbon compounds (, , ) are strong. The abundance of carbon relative to oxygen is 4–5 times greater in the C stars than in normal stars. The C stars are divided into two groups, hotter R stars and cooler N stars.

- Another type of giant stars with abundance anomalies are the barium stars. The lines of barium, strontium, rare earths and some carbon compounds are strong in their spectra. Apparently nuclear reaction products have been mixed up to the surface in these stars.

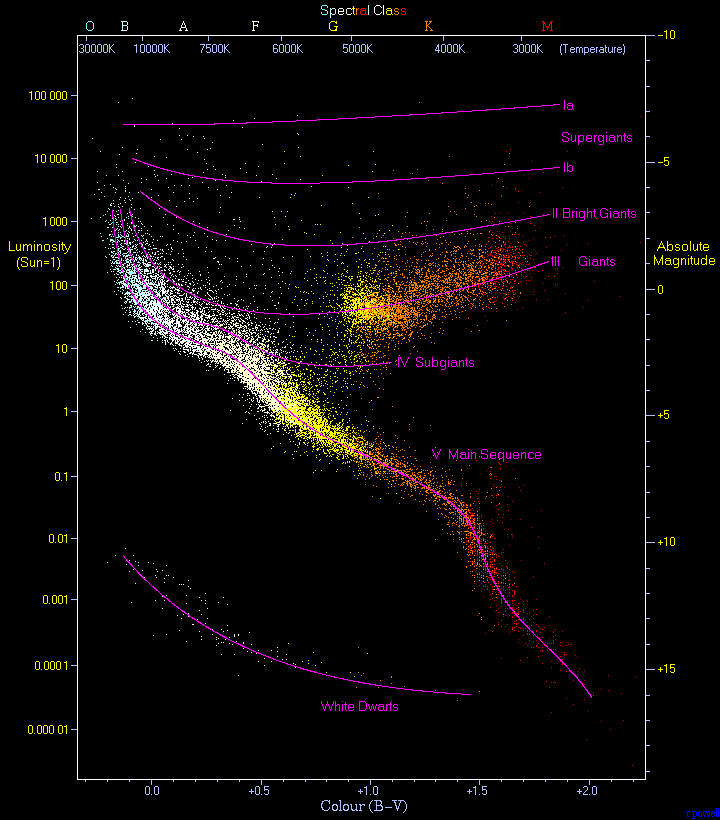

Hertzsprung-Russell Diagram

The Hertzsprung–Russell diagram or HR diagram is a scatter plot of stars showing the relationship between the stars’ absolute magnitudes or luminosities and their stellar classifications or effective temperatures.

The empirical mass-luminosity relation states

where the luminosity and mass are measured in and respectively.

Variables

Stars with changing magnitudes are called variables. When a new variable is discovered, it is given a name according to the constellation in which it is located. The name of the first variable in a given constellation is R, followed by the name of the constellation (in the genitive case). The symbol for the second variable is S, and so on, to Z. After these, the two-letter symbols RR, RS, … to ZZ are used, and then AA to QZ (omitting I). The numbering continues with V335, V336, etc. (V stands for variable). The classification of variables is based on the shape of the lightcurve, and on the spectral class and observed radial motions.

Pulsating Variables

The wavelengths of the spectral lines of the pulsating variables change along with the brightness variations. These changes are due to the Doppler effect, showing that the outer layers of the star are indeed pulsating. The period of pulsation corresponds to a proper frequency of the star. The period of pulsation is inversely propotional to the square root of the mean density.

- Cephieds: These are pulsating variables named after Cephei. They are population I supergiants of spectral class F-K. Their periods are 1–50 days and their amplitudes, 0.1–2.5 magnitudes. Cephieds are of two types - Type I and Type II. Both types of cephieds follow a relationship between absolute magnitude and pulsating period, called period-luminosity relationship. It can be used to measure distances of stars and nearby galaxies. It reads as follows:

-

RR Lyrae: Their brightness variations are smaller than those of the cepheids, usually less than a magnitude. Their periods are also shorter, less than a day. RR Lyrae stars are old population II stars. They are very common in the globular star clusters and were therefore previously called cluster variables. The absolute magnitude of all RR Lyrae stars are about . They are all of roughly the same age and mass, and thus represent the same evolutionary phase, where helium is just beginning to burn in the core. Since the absolute magnitudes of the RR Lyrae variables are known, they can be used to determine distances to the globular clusters.

-

Mira Variables: The Mira variables (named after Mira Ceti) are supergiants of spectral classes M, S or C. They are losing gas in a steady stellar wind. Their periods are normally 100–500 days, and for this reason, they are also sometimes called long period variables. The amplitude of the light variations is typically about 6 magnitudes in the visual region. The period of Mira itself is about 330 days and its diameter is about 2 au. At its brightest, Mira has the magnitude 2–4, but at light minimum, it may be down to 12. The effective temperature of the Mira variables is only about 2000 K. Thus 95 % of their radiation is in the infrared, which means that a very small change in temperature can cause a very large change in visual brightness.

Eruptive Variables

In the eruptive variables there are no regular pulsations. Instead sudden outbursts occur in which material is ejected into space. Such stars are divided into two main categories, eruptive and cataclysmic variables. Brightness changes of eruptive variables are caused by sudden eruptions in the chromosphere or corona, the contributions of which are, however, rather small in the stellar scale. These stars are usually surrounded by a gas shell or interstellar matter participating in the eruption.

-

Flare Stars: The flarestars are dwarf stars of spectral class M. They are young stars, mostly found in young star clusters and associations. At irregular intervals there are flare outbursts on the surface of the stars similar to those on the Sun. The flares are related to disturbances in the surface magnetic fields. The energy of the outbursts of the flare stars is about the same as in solar flares, but because the stars are much fainter than the Sun, a flare can cause a brightening by up to 4–5 magnitudes. A flare lights up in a few seconds and then fades away in a few minutes.

-

R Corona Borealis Type: Stars of the R Coronae Borealis type have “inverse nova” light curves. Their brightness may drop by almost ten magnitudes and stay low for years, before the star brightens to its normal luminosity. For example, R CrB itself is of magnitude 5.8, but may fade to 14.8 magnitudes. The R CrB stars are rich in carbon and the decline is produced when the carbon condenses into a circumstellar dust shell.

-

Novae: The outbursts of all novae are rapid. Within a day or two the brightness rises to a maximum, which may be 7–16 magnitudes brighter than the normal luminosity. This is followed by a gradual decline, which may go on for months or years.

Cataclysmic Variables

When a white dwarf is a member of a close binary system, it can accrete mass from its companion star. The most interesting case is where a main sequence star is filling its Roche lobe, the largest volume it can have without spilling over to the white dwarf. As the secondary evolves, it expands and begins to lose mass, which is eventually accreted by the primary. Binary stars of this kind are known as cataclysmic variables.

Supernovae

Type Ia supernovae are recognised by the silicon absorption line (615 nm), which is strong in the spectra of young novae. These supernovae originate in binaries consisting of a white dwarf and its companion.

In such a close binary material can flow from the companion to the white dwarf until it mass exceeds the Chandrasekhar limit (discussed later). As a result, the pressure of the degenerate electron gas inside the white dwarf can no longer overcome the gravitation and star collapses. Increase in the density and temperature ignites an explosive fusion reaction that destroys the white dwarf. The kinetic energy released in the process is of the order of J. This enormous burst of energy can cause part of the gas to expand even at a velocity of around c.

The origin of this energy (around J) is the fission of the radioactive nickel isotope 56 created in the explosion into radioactive cobalt and further into stable iron. The more nickel is produced in the explosion the brighter the supernova shines at its maximum; typically the absolute magnitude reaches −19 to −20.

The shape of the lightcurve depends on the brightness of the supernova: the brighter the supernova the broader the top of the lightcurve. Therefore the maximum brightness of a type Ia supernova can be determined precisely from its lightcurve. This way they can be used as standard candles to determine dimensions of the universe and cosmological parameters

All supernovae except type Ia are caused by the collapse of massive and short lived stars. At the end of its lifespan such a star has an iron core that will collapse under its own gravity after exceeding the Chandrasekhar limit. In the stellar core the matter will reach the density of atomic nuclei and the outer layers bounce back sending an outbound shock wave. The process creates a huge number of neutrinos, which rush to the surrounding space. The outer layers of the star receive a kinetic energy of about J, part of which may be released as radiation when the expanding matter hits the material surrounding the star and later the interstellar matter. Typically the supernova itself emits radiation about J within a few months after the explosion, reaching an absolute magnitude between −16 and −20 at the maximum. Later the brightness is sustained by the fission of the radioactive nickel 56, born in the explosion, to other elements just as in the case of the type Ia supernovae.

Compact Stars

White Dwarfs

When the star runs out of its nuclear fuel, the density in the interior increases, but the temperature does not change much. The electrons become degenerate, and the pressure is mainly due to the pressure of the degenerate electron gas, the pressure due to the ions and radiation being negligible. The star becomes a white dwarf. The radius of a degenerate star is inversely proportional to the cubic root of the mass. Unlike in a normal star the radius decreases as the mass increases. White dwarfs have no internal sources of energy, but further gravitational contraction is prevented by the pressure of the degenerate electron gas. Radiating away the remaining heat, white dwarfs will slowly cool, changing in colour from white to red and finally to black.

White dwarfs cannot be more massive than about 1.4 . If the mass is larger, the electrons become relativistic and the pressure of the degenerate electron gas is no longer able to resist the gravitational attraction. The star will then rapidly contract towards higher densities. The final stable state reached after this collapse will be a neutron star or a black hole, depending on the mass of the star. The maximum mass of a white dwarf is called the Chandrasekhar limit, given by

Neutron Stars

If the mass of a star is large enough, the density of matter may grow even larger than in normal white dwarfs. The equation of state of a classical degenerate electron gas then has to be replaced with the corresponding relativistic formula. In this case decreasing the radius of the star no longer helps in resisting the gravitational attraction. Equilibrium is possible only for one particular value of the mass, the Chandrasekhar mass . If the mass of the star is larger than this, gravity overwhelms the pressure and the star will rapidly contract towards higher densities. The final stable state reached after this collapse will be a neutron star. On the other hand, if the mass is smaller than , the pressure dominates. The star will then expand until the density is small enough to allow an equilibrium state with a less relativistic equation of state.

Neutron stars are supported against gravity by the pressure of the degenerate neutron gas, just as white dwarfs are supported by electron pressure. The equation of state is the same, except that the electron mass is replaced by the neutron mass, and that the mean molecular weight is defined with respect to the number of free neutrons. Since the gas consists almost entirely of neutrons, the mean molecular weight is approximately one. The typical diameters of neutron stars are about 10 km. Unlike ordinary stars they have a well-defined solid surface. The atmosphere above it is a few centimetres thick. The upper crust is a metallic solid with the density growing rapidly inwards.

-

Pulsar: A pulsar is a highly magnetized rotating neutron star that emits beams of electromagnetic radiation out of its magnetic poles. This radiation can be observed only when a beam of emission is pointing toward Earth (similar to the way a lighthouse can be seen only when the light is pointed in the direction of an observer), and is responsible for the pulsed appearance of emission. Neutron stars are very dense and have short, regular rotational periods. This produces a very precise interval between pulses that ranges from milliseconds to seconds for an individual pulsar.

-

Magnetar: A magnetar is a type of neutron star with an extremely powerful magnetic field (~ to T). The magnetic-field decay powers the emission of high-energy electromagnetic radiation, particularly X-rays and gamma rays. Magnetars are differentiated from other neutron stars by having even stronger magnetic fields, and by rotating more slowly in comparison. Most observed magnetars rotate once every two to ten seconds, whereas typical neutron stars, observed as radio pulsars, rotate one to ten times per second.

Gamma Ray Bursts (GRBs)

Gamma-ray bursts (GRBs) are extremely energetic events occurring in distant galaxies which represent the brightest and most powerful class of explosion in the universe. These extreme electromagnetic emissions are second only to the Big Bang as the most energetic and luminous phenomenon ever known. Gamma-ray bursts can last from a few milliseconds to several hours. After the initial flash of gamma rays, a longer-lived afterglow is emitted, usually in the longer wavelengths of X-ray, ultraviolet, optical, infrared, microwave or radio frequencies. The intense radiation of most observed GRBs is thought to be released during a supernova or superluminous supernova, called hypernova, as a high-mass star implodes to form a neutron star or a black hole. Short-duration (sGRB) events are a subclass of GRB signals that are now known to originate from the cataclysmic merger of binary neutron stars.

Black Holes

A black hole is a massive, compact astronomical object so dense that its gravity prevents anything from escaping, even light. Albert Einstein’s theory of general relativity predicts that a sufficiently compact mass will form a black hole. The boundary of no escape is called the event horizon. Black holes typically form when massive stars collapse at the end of their life cycle. After a black hole has formed, it can grow by absorbing mass from its surroundings. Supermassive black holes of millions of solar masses may form by absorbing other stars and merging with other black holes, or via direct collapse of gas clouds. There is consensus that supermassive black holes exist in the centres of most galaxies.

The Schwarzchild radius of the even horizon of a black hole is given by

This is the radius of the event horizon of the black hole, a point of no return for anything that crosses it.

In many ways, a black hole acts like an ideal black body, as it reflects no light. Quantum field theory in curved spacetime predicts that event horizons emit Hawking radiation, with the same spectrum as a black body of a temperature inversely proportional to its mass. This temperature is of the order of billionths of a kelvin for stellar black holes, making it essentially impossible to observe directly. The Hawking temperature of a black hole is given by

The no hair theorem states that a black hole can only have three observable quantities: mass, angular momentum and charge.

Near the event horizon the different time definitions become significant. An observer falling into a black hole reaches the centre in a finite time, according to his own clock, and does not notice anything special as he passes through the event horizon. However, to a distant observer he never seems to reach the event horizon; his velocity of fall seems to decrease towards zero as he approaches the horizon. The slowing down of time also appears as a decrease in the frequency of light signals. The formula for the gravitational redshift can be written in terms of the Schwarzschild radius as

Here, is the frequency of radiation emitted at a distance r from the black hole and the frequency observed by an infinitely distant observer. It can be seen that the frequency at infinity approaches zero for radiation emitted near the event horizon.

X-ray Binaries

Close binaries where a neutron star or a black hole is accreting matter from its companion, usually a main sequence star, will be visible as strong X-ray sources. They are generally classified as high-mass X-ray binaries (HMXB), when the companion has a mass larger than about , and low-mass X-ray binaries (LMXB) with a companion mass smaller than . In HMXBs the source of the accreted material is a strong stellar wind. LMXBs are produced by Roche-lobe overflow of the companion star, either because the major axis of the binary decreases due to angular momentum loss from the system, or else because the radius of the companion is increasing as it evolves.