Galaxies

Galaxies are huge groups of stars, gas, dust, and dark matter bound together by gravity. Typically, they contain billions to trillions of stars, along with their planetary systems and interstellar gas and dust. Galaxies can range in size from dwarfs with just a few billion stars to the largest galaxies known, which can contain one hundred trillion stars or more.

Most galaxies are between 10 billion and 13.6 billion years old. Some are almost as old as the universe itself, which formed around 13.8 billion years ago. Astronomers think the youngest known galaxy formed approximately 500 million years ago.

Galaxies can organize into groups of about 100 or fewer members held together by their mutual gravity. Larger structures, called clusters, may contain thousands of galaxies. Groups and clusters can be arranged in superclusters, which are not gravitationally bound. At the largest scales, the superclusters are arranged into sheets and filaments—the largest known structures in the universe.

Galaxy filaments are massive, thread-like structures spanning around 50 to 80 megaparsecs, with the largest being the Hercules-Corona Borealis Great Wall at around 3 gigaparsecs in length (although still unconfirmed). The filaments are separated by cosmic voids, which are vast spaces that contain very few or no galaxies, the largest being the KBC void (also known as the Local Hole).

The Milky Way is part of the Local Group, which is part of the Virgo Supercluster, which in turn is part of the Laniakea Supercluster. The KBC void contains the Milky Way and the Local Group, and the larger part of the Laniakea Supercluster.

Hubble Classification of Galaxies

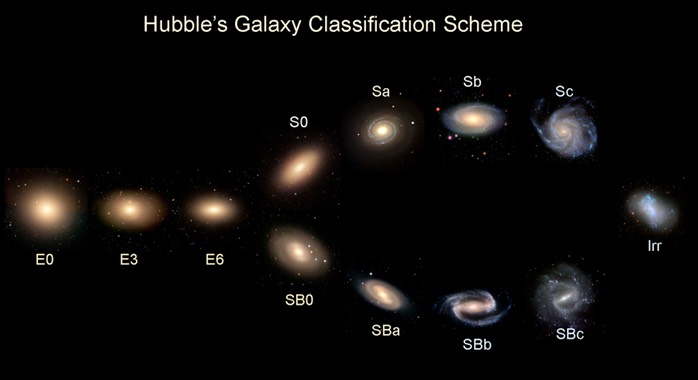

The Hubble classification scheme is a system used to classify galaxies based on their morphology. It was developed by Edwin Hubble in the 1920s and is still widely used today. The Hubble classification scheme divides galaxies into several main categories, including:

- Elliptical galaxies (E): These galaxies are characterized by their smooth, featureless appearance and are typically composed of older stars. They are classified based on their ellipticity, with E0 being nearly spherical and E7 being highly elongated. If the major and minor axes of the galaxy are and respectively, then its type is given by E, where .

- Lenticular galaxies (S0): These galaxies have a disk-like structure similar to spiral galaxies but lack the prominent spiral arms. They are often considered a transitional type between elliptical and spiral galaxies.

- Spiral galaxies (S): These galaxies are characterized by their spiral arms and a central bulge. They are classified based on the tightness of their spiral arms and the size of their central bulge. These can be further classified as Sa, Sb and Sc, where Sa has tightly wound spiral arms and a large central bulge, Sb has moderately wound spiral arms and a medium-sized central bulge, and Sc has loosely wound spiral arms and a small central bulge.

- Spiral Barred galaxies (SB): These galaxies have a central bar-shaped structure that extends from the nucleus to the spiral arms. They are classified in the same way as normal spiral galaxies, with the addition of the “SB” prefix. These can be further classified as SBa, SBb and SBc, where SBa has tightly wound spiral arms and a large central bulge, SBb has moderately wound spiral arms and a medium-sized central bulge, and SBc has loosely wound spiral arms and a small central bulge.

- Irregular galaxies (Irr): These galaxies do not fit into any of the above categories and have an irregular shape. They are often rich in gas and dust and are typically associated with active star formation.

A few more classifications, which are not part of the OG hubble classification are:

- SAB galaxies: These are spiral barred galaxies that have a weak central bar-shaped structure that extends from the nucleus to the spiral arms. They lie between S and SB galaxies in terms of their morphology.

- Sm galaxies: These are irregular galaxies that have a more regular shape than typical irregular galaxies. They are often rich in gas and dust and are typically associated with active star formation. These are shaped like the Magellanic clouds.

- dIrr galaxies: These are dwarf irregular galaxies that are found in the outskirts of galaxy clusters. They are typically small and have a low luminosity.

- dE galaxies: Dwarf elliptical galaxies

- dSph galaxies: Dwarf spheroidal galaxies

Galactic Relations

We define the galaxy effective radius or half light radius as the radius at which half of the total light of a galaxy is emitted. The radius is defined as the disk radius corresponding to a surface brightness of .

The mass to light ratio is a marker of the amount of mass per brightness contained within the radius . It is given by the total mass of the galaxy divided by its total luminosity. This ratio is approximately constant for each class of spiral galaxy, when integrating across the entire galaxy. The mass to light ratio is a useful tool for estimating the total mass of a galaxy, including dark matter, and can be used to study the dynamics and evolution of galaxies.

The de-Vaucouleurs profile describes how the surface brightness of an elliptical galaxy varies as a function of apparent distance from the center of the galaxy. It is given by the equation

The Tully-Fisher relation relates the luminosity of a spiral galaxy to its peak rotational speed . The Tully-Fisher relation can be expressed mathematically as

or , where , and are constants.

The Faber-Jackson relation relates the luminosity of an elliptical galaxy to its velocity dispersion . The Faber-Jackson relation can be expressed mathematically as

For quasars, the part of the quasar that is varying in brightness must be smaller than the distance light travels in the time it takes for the variation to occur.

Milky Way

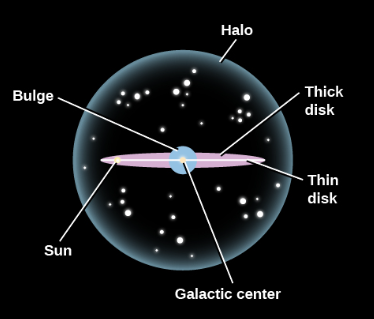

The Milky Way is a barred spiral galaxy or type SBbc or SBc that is home to our solar system. It is composed of several components, including the galactic bulge, disk, and halo. The galactic bulge is a dense and bright region of stars located at the center of the galaxy. The disk is a flat region that contains most of the galaxy’s stars and gas, a few kiloparsecs thick. The stars found in the disk are relatively younger. The halo is a spherical region that surrounds the galaxy and contains globular clusters, older and redder stars, and dark matter. It is almost spherical.

Sun’s orbital speed around the galactic center is around 220 km/s, and is at a distance of about 8.5 kpc from the galactic center.

Let the angular velocity of a star in circular orbit around the center of the galaxy be

It has been observed that the angular velocity of rotation depends on the distance from the galactic center. Such rotation is called differential rotation. Thus the rotation curve of the galaxy is not keplerian, but rather flattens out after a few kiloparsecs.

For stars and gas in the disk of our galaxy to be in stable circular orbits (assuming spherical mass distribution),

It has been observed that in the region outside sun’s orbital radius, the orbital velocity is roughly constant, hence the mass enclosed must increase. However, the luminosity decreases exponentially. This “extra” non-luminous mass is termed as dark matter. Approximately 85% of all matter in the universe is in the form of dark matter.

Oort Equations

The Local Standard of Rest (LSR) is the reference frame in which the mean velocity of the stars in the solar neighborhood is zero. The velocity of the individual stars relative to the LSR is called the peculiar velocity of the star. The point towards which the Sun is moving relative to the LSR is called the solar apex. The opposite point on the celestial sphere is called the solar antapex. Sun’s velocity with respect to the LSR is around 20 km/s, with the apex being located in the constellation Hercules.

Let the sun’s orbital speed and orbital radius be and respectively. For a star in the galactic plane at galactic longitude and distance from the sun, its relative velocity with respect to sun is given by

where and are the first and second Oort constants respectively.

The angular velocity of LSR around the galactic center () can thus be found.

ISM

The interstellar medium (ISM) is the matter that exists in the space between the stars in a galaxy. It is composed of gas, dust, and cosmic rays. The ISM causes extinction and reddening of light from distant stars, which can affect the observed properties of those stars. This is mainly in two ways

- Absorption: The radiant energy is absorbed by the ISM and re-radiated in infrared wavelengths (corresponding to the temperature of the ISM particles).

- Scattering: The direction of light propagation is changed by the ISM particles, which causes the light to be scattered in different directions. This causes a reduction in the intensity of light reaching the observer.

Assume all dust particles are spheres of radius . The extinction cross section of the particles is given by

where is the extinction efficiency factor, which is a function of the wavelength of light. It can be calculated using rayleigh scattering or mie scattering. If the number density of particles is , the optical depth is given by

where is a small distance in the direction of propagation of light, is the total distance travelled by light, and is the average number density of particles along the path of light. The optical depth is a measure of the amount of light absorbed or scattered by the ISM. The total extinction is given by

Extinction highly depends on the wavelength of light. Blue light is scattered more than red light. Hence the ISM is also responsible for the reddening of the light of stars.

where and are the magnitudes of the star in the blue and visual bands respectively, is the intrinsic color of the star, is the color excess, and is the ratio of total to selective extinction.

Interstellar gas can be detected via the following methods

- Absorption lines: The ISM absorbs light from stars, which can be detected as absorption lines in the spectrum of the star. The strength and shape of the absorption lines can provide information about the composition and physical conditions of the ISM.

- Emission lines: The ISM can also emit light, which can be detected as emission lines in the spectrum of the ISM. The strength and shape of the emission lines can provide information about the composition and physical conditions of the ISM.

- Bremsstrahlung radiation: The ISM can emit bremsstrahlung radiation, which is a type of radiation produced by the acceleration of charged particles. This radiation can be detected in the radio and X-ray wavelengths.

- 21 cm line: The ISM can emit radiation at a wavelength of 21 cm, which is produced by the hyperfine transition of neutral hydrogen. This radiation can be detected in the radio wavelengths and is used to map the distribution of neutral hydrogen in the ISM.

- Radio line emission: The ISM can emit radiation at various wavelengths, which can be detected in the radio wavelengths. This radiation is produced by various processes, including synchrotron radiation and thermal emission from dust.

The 21 cm line is a spectral line that is produced by the hyperfine transition of neutral hydrogen. It is emitted when the spin of the electron and proton in a hydrogen atom are parallel (triplet state) and flips to the state where they are anti-parallel (singlet state). The energy difference between these two states is very small, which corresponds to a wavelength of 21 cm. It is a very important tool for studying the ISM, as it allows astronomers to map the distribution of neutral hydrogen in the ISM.

Types of Galaxies

Except the hubble classification scheme, galaxies can be classified into several other types based on their properties and characteristics. Some of the most common types of galaxies include:

- CD galaxies: These are dwarf elliptical galaxies that are found in the central regions of galaxy clusters. They are typically small and have a low luminosity.

- uFd galaxies: These are ultra-faint dwarf galaxies that are found in the outskirts of galaxy clusters. They are typically very small and have a very low luminosity.

- UCD galaxies: These are ultra-compact dwarf galaxies that are found in the central regions of galaxy clusters. They are typically very small and have a very low luminosity.

- Radio galaxies: These are galaxies that emit strong radio waves, often associated with active galactic nuclei (AGN) or supermassive black holes. They can be classified into two main types: Fanaroff-Riley type I (FRI) and type II (FRII) radio galaxies, based on their radio morphology and luminosity.

- Quasars: Quasars are extremely luminous and distant active galactic nuclei (AGN) powered by supermassive black holes. They are among the most energetic objects in the universe and can outshine entire galaxies.

- Seyfert galaxies: These are a type of active galaxy that exhibits strong emission lines in their spectra. They are classified into two main types: Seyfert 1 and Seyfert 2, based on the strength and width of their emission lines. Seyfert I galaxies have broad emission lines, while Seyfert II galaxies have narrow emission lines.

- Blazars: These are a type of active galaxy that emits strong and variable radiation across the electromagnetic spectrum, including radio, optical, and X-ray wavelengths. They are thought to be powered by supermassive black holes and are often associated with jets of relativistic particles.

- AGN: Active Galactic Nuclei (AGN) are the central regions of galaxies that are extremely bright and energetic due to the presence of supermassive black holes. AGN can be classified into several types, including Seyfert galaxies, quasars, and blazars, based on their properties and characteristics.